I have been wanting to share the work of Uta Barth for sometime now, ever since I saw her exquisite exhibition at the Chicago Art Institute this past summer. It happened to coincide with my long swims in Lake Michigan where I would study the light patterns not only on the surface of the water but also on the sand under the shallow waters.

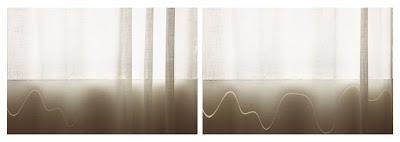

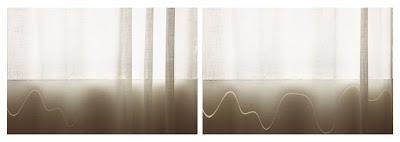

I was memorized by the quiet elegant images that Barth created from what I can gather, a place of deep meditation. In one room, you are surrounded by the bands of light that are reflected in hanging curtains, an ordinary sight that was transformed into the extraordinary. It reminded me of a exhibition I saw many years ago at the Met where I was in a room surrounded by Monet's Water Lilies.

I am so appreciative to share the following essays provided by Uta Barth that further illuminate her work.

Barth writes

"…to walk without destination and to see only to see.

I am interested in visual perception.

I am interested in getting you to engage in looking rather than losing your attention to thoughts about what you are looking at.

Seeing Is Forgetting the Name of the Thing One Sees is the title of Lawrence Weschler’s biography of Robert Irwin. Long before that, it was a line in a Zen text. Nothing could better describe what I aim for with each project I make, over and over, yet each time in a different way.

If the subject of the work is perception and not what the camera is pointed at, then there is no point in “going out to photograph.” Given that, ten years ago I made the “choice of no choice”: I would only photograph wherever I happened to be most of the time, the interior of my own home.

But you still have to point the lens someplace. So you let it follow your gaze, allow it to stare at the same thing for hours and months, or to simply trace light and time. To render light, time, silence, and negative space; to see the volume of a room instead of its walls and then to trace vision where the camera cannot follow and to look at what you see with one’s eyes closed, by tracing the play of afterimages the human eye plays out for us. All of this is what I have pursued.

Always about vision, being immersed in vision, always about “now.” This is what motivates the work and what motivates my day."

The color of light in Helsinki

Uta Barth 2004

‘What about perception?’

For years I have been talking about my work in terms of perception and countering other, more romantic, interpretations of it. Visual perception has been and continues to be the primary point of entry for thinking about the art I make, and for most of the things I do and I think about. Some time ago, while working on a text about my work, critic Timothy Martin asked me what I thought was a startling – and quite annoying – question: ‘What about perception?’ I had always completely taken for granted the answer to this question; so, although I can’t claim to explain all the aspects that interest me, I thought I’d make a sideways, sort of drifty stab at responding to some parts of that question here.1

Inside out

I remember:

The colour of light on the harbour in Helsinki.

The warm grey of the sky in Berlin.

Dense heat and humidity in the Yucatan. Standing there, in a field, being drenched with rain that was warmer than even my skin.

Driving into a cloud of white butterflies, so large, so dense that it obscured all vision of the road and the sky.

The glowing yellow light that streaks across my bedroom walls at 5:30 in the morning.

The sound of car tyres moving across an empty desert road on a hot summer night.

A cool night, bright moon, warm pool. Watching the steam rising.

The smell of the desert ground after a rainstorm.

Bare feet on warm sticky pavement. A Hollywood side street late one Saturday night.

Floating in a pool in the desert during a summer thunderstorm. Cool water falling on wet skin.

Looking into your eyes and the light reflecting in them. Looking past that light.

Something so far off in the distance, barely discernable, barely visible. Deep space.

Watching you walk away, walk into the dense rain. Watching your silhouette disappear into it.

The sudden feeling that someone is looking at you from behind.

Charcoal grey clouds moving towards me as I looked over your shoulder while we talked.

Squinting into piercing bright light. The look of the bleached and white landscape in Mexico.

Being on a fast train in Europe. A rainy landscape flying, streaking by in a flash of green.

The pale, slow fade of grey where the Glendale smog meets the sky.

Heat radiating, waving up from black asphalt, on a hot desert road. The smell of that.

A wall of water falling through the sky. Watching a storm in the distance.

The green glowing after-image of light caused by staring too hard and too long into a blinding, bright sky.

I remember each of these moments with a crystal clarity and completeness that even the present too often lacks. To this day I can see them, hear them; I can feel the humidity on my skin. Yet I remember little or nothing of the surrounding events.

Clearly these might be scenes that lend themselves neatly to romantic or melancholic interpretation – perhaps even nostalgia and longing? They would nicely set the tone for song lyrics that one might write (‘For you’), or be the opening lines of a novel; after all they would all start with ‘I remember’, and each scene is quite solitary in nature. All the right stuff: what desire is made of. Since I am cursed with the capacity for pining, I might find this way of seeing it a useful one.

But …

But, perhaps, there is another way to look at this list (a list that could potentially continue ad infinitum.)

I assume all of us have such a list; but this one is mine.

Perhaps it exists because these are fragments of time when I was ripped from the flow of narrative into a single moment. A moment when sound and vision were inverted themselves, torn inside out and filled my attention to capacity. A moment when everything else dropped away and the experience of seeing, of sensing, became so overwhelming, so all-encompassing, that the very idea of interpretation did not, could not, exist.

This is an interesting space of mind: when we lose all assumed meaning; lose the inevitability of narrative; lose the impulse for interpretation. A space of mind that is dislodged from making meaning and yet sees beyond the 180 degrees before us.

This space of mind produces a strange kind of vision, where positive and negative space hold equal weight. Where you can see the air and hear the interval between the sounds of passing cars on a dark desert road late at night. Where rain is not a sign of longing but something that fills and articulates what was previously negative space. Where light and dark are not about mood, but blind and flood your field of vision.

and, “What are you doing?”

Late one night, while writing his essay on Untitled, 1998, for this book, Jeremy Gilbert-Rolfe called to ask me: ‘What is it you are doing before or when you are making these photographs?’ The answer to this question is: I am doing absolutely nothing. I am not even lost in thought, but sort of lost in looking. I am quite literally doing what we call ‘absentmindedly staring into space’. That is how I spend much of my time; it is incredibly unproductive and it wreaks havoc on my ever-looming work ethic. It is also a state of mind not given to the impulse of making photographs. To me, nothing about being suspended and engaged in the visual, auditory or sensory observation of the moment lends itself to the desire to freeze or save it. I don’t have this type of relationship to making photographs, one of wanting to capture or replicate fleeting events. That would seem irrelevant and quite futile. The activity of making a photograph, to me, is one of disruption. The desire is not to capture or reproduce the moment, but perhaps, or hopefully, to create the potential for generating a new and quite different moment. Somehow the difference between these two desires seems an important distinction to me.

Again and again

Duration, endless repetition, sameness and redundancy, all for their own sake, are of interest here. Close attention which is not motivated by a developing story line. The scene does not change, but the raw impression of sight does with the blink of the eye. What happens when you stare into the light too long? The image burns onto your retina while its opposite drifts inside your eye and your mind. This ‘drifting opposite’ becomes the only event. An event worth watching, as it moves on its own and then recuperates and reconstitutes in the very next glimpse. It is not a narrative progression but a continual looping back to what is – almost – the original scene.

Scientists tell us that if you paralyze the eye and prevent it from moving continuously, scanning the scene much like a small motion detector, vision dissolves into a field of white light. They say that the eye and the brain only register difference and change. What is known and familiar is quite literally invisible. They also say that it is impossible to locate the point of distinction where the cells of the optic nerve turn into the cells of the brain.

Something about rain

‘Is the work about being inside on a wet day?’, Jeremy asks in his essay for this book.

In some ways, what could be better? And: what else could it be?

I’ve loved rainy weather all my life. Perhaps it is because I grew up with it in Berlin, a city wet and grey more often than not. But, more importantly, because watching the rain begin to fall on a scene outside a window slowly inverts all of the space before my eyes. Small drops, then streaks and lines begin to articulate what started out as the invisible volume of air: the negative space in the scene. My attention moves and my eyes begin to focus on a plane that was previously unoccupied, a plane in space that only seconds ago had no mark to guide the eye. In a short time, that which was empty fills with thick dense lines as it obscures what was previously the view. Wet blobs fill the volume to which everything else now becomes the backdrop. The glass of the window becomes a flat plane on which a screen of drops run and pour with increasing insistence and density, separating the two quite different events. All spatial understanding is reoriented. The ambient sound of raindrops falling is not directional but comes from all around. Their insistent sound repeatedly draws our attention to the present moment. This, it seems to me, is a pretty interesting thing to watch and listen to, from ‘ … the inside, on a wet day’.

Martin, Timothy, What about perception, working title for a forthcoming collection of essays, some previously published in Uta Barth: In Between Places, Henry Art Gallery, University of Washington, Seattle, 2000.

I was memorized by the quiet elegant images that Barth created from what I can gather, a place of deep meditation. In one room, you are surrounded by the bands of light that are reflected in hanging curtains, an ordinary sight that was transformed into the extraordinary. It reminded me of a exhibition I saw many years ago at the Met where I was in a room surrounded by Monet's Water Lilies.

I am so appreciative to share the following essays provided by Uta Barth that further illuminate her work.

Barth writes

"…to walk without destination and to see only to see.

I am interested in visual perception.

I am interested in getting you to engage in looking rather than losing your attention to thoughts about what you are looking at.

Seeing Is Forgetting the Name of the Thing One Sees is the title of Lawrence Weschler’s biography of Robert Irwin. Long before that, it was a line in a Zen text. Nothing could better describe what I aim for with each project I make, over and over, yet each time in a different way.

If the subject of the work is perception and not what the camera is pointed at, then there is no point in “going out to photograph.” Given that, ten years ago I made the “choice of no choice”: I would only photograph wherever I happened to be most of the time, the interior of my own home.

But you still have to point the lens someplace. So you let it follow your gaze, allow it to stare at the same thing for hours and months, or to simply trace light and time. To render light, time, silence, and negative space; to see the volume of a room instead of its walls and then to trace vision where the camera cannot follow and to look at what you see with one’s eyes closed, by tracing the play of afterimages the human eye plays out for us. All of this is what I have pursued.

Always about vision, being immersed in vision, always about “now.” This is what motivates the work and what motivates my day."

The color of light in Helsinki

Uta Barth 2004

‘What about perception?’

For years I have been talking about my work in terms of perception and countering other, more romantic, interpretations of it. Visual perception has been and continues to be the primary point of entry for thinking about the art I make, and for most of the things I do and I think about. Some time ago, while working on a text about my work, critic Timothy Martin asked me what I thought was a startling – and quite annoying – question: ‘What about perception?’ I had always completely taken for granted the answer to this question; so, although I can’t claim to explain all the aspects that interest me, I thought I’d make a sideways, sort of drifty stab at responding to some parts of that question here.1

Inside out

I remember:

The colour of light on the harbour in Helsinki.

The warm grey of the sky in Berlin.

Dense heat and humidity in the Yucatan. Standing there, in a field, being drenched with rain that was warmer than even my skin.

Driving into a cloud of white butterflies, so large, so dense that it obscured all vision of the road and the sky.

The glowing yellow light that streaks across my bedroom walls at 5:30 in the morning.

The sound of car tyres moving across an empty desert road on a hot summer night.

A cool night, bright moon, warm pool. Watching the steam rising.

The smell of the desert ground after a rainstorm.

Bare feet on warm sticky pavement. A Hollywood side street late one Saturday night.

Floating in a pool in the desert during a summer thunderstorm. Cool water falling on wet skin.

Looking into your eyes and the light reflecting in them. Looking past that light.

Something so far off in the distance, barely discernable, barely visible. Deep space.

Watching you walk away, walk into the dense rain. Watching your silhouette disappear into it.

The sudden feeling that someone is looking at you from behind.

Charcoal grey clouds moving towards me as I looked over your shoulder while we talked.

Squinting into piercing bright light. The look of the bleached and white landscape in Mexico.

Being on a fast train in Europe. A rainy landscape flying, streaking by in a flash of green.

The pale, slow fade of grey where the Glendale smog meets the sky.

Heat radiating, waving up from black asphalt, on a hot desert road. The smell of that.

A wall of water falling through the sky. Watching a storm in the distance.

The green glowing after-image of light caused by staring too hard and too long into a blinding, bright sky.

I remember each of these moments with a crystal clarity and completeness that even the present too often lacks. To this day I can see them, hear them; I can feel the humidity on my skin. Yet I remember little or nothing of the surrounding events.

Clearly these might be scenes that lend themselves neatly to romantic or melancholic interpretation – perhaps even nostalgia and longing? They would nicely set the tone for song lyrics that one might write (‘For you’), or be the opening lines of a novel; after all they would all start with ‘I remember’, and each scene is quite solitary in nature. All the right stuff: what desire is made of. Since I am cursed with the capacity for pining, I might find this way of seeing it a useful one.

But …

But, perhaps, there is another way to look at this list (a list that could potentially continue ad infinitum.)

I assume all of us have such a list; but this one is mine.

Perhaps it exists because these are fragments of time when I was ripped from the flow of narrative into a single moment. A moment when sound and vision were inverted themselves, torn inside out and filled my attention to capacity. A moment when everything else dropped away and the experience of seeing, of sensing, became so overwhelming, so all-encompassing, that the very idea of interpretation did not, could not, exist.

This is an interesting space of mind: when we lose all assumed meaning; lose the inevitability of narrative; lose the impulse for interpretation. A space of mind that is dislodged from making meaning and yet sees beyond the 180 degrees before us.

This space of mind produces a strange kind of vision, where positive and negative space hold equal weight. Where you can see the air and hear the interval between the sounds of passing cars on a dark desert road late at night. Where rain is not a sign of longing but something that fills and articulates what was previously negative space. Where light and dark are not about mood, but blind and flood your field of vision.

and, “What are you doing?”

Late one night, while writing his essay on Untitled, 1998, for this book, Jeremy Gilbert-Rolfe called to ask me: ‘What is it you are doing before or when you are making these photographs?’ The answer to this question is: I am doing absolutely nothing. I am not even lost in thought, but sort of lost in looking. I am quite literally doing what we call ‘absentmindedly staring into space’. That is how I spend much of my time; it is incredibly unproductive and it wreaks havoc on my ever-looming work ethic. It is also a state of mind not given to the impulse of making photographs. To me, nothing about being suspended and engaged in the visual, auditory or sensory observation of the moment lends itself to the desire to freeze or save it. I don’t have this type of relationship to making photographs, one of wanting to capture or replicate fleeting events. That would seem irrelevant and quite futile. The activity of making a photograph, to me, is one of disruption. The desire is not to capture or reproduce the moment, but perhaps, or hopefully, to create the potential for generating a new and quite different moment. Somehow the difference between these two desires seems an important distinction to me.

Again and again

Duration, endless repetition, sameness and redundancy, all for their own sake, are of interest here. Close attention which is not motivated by a developing story line. The scene does not change, but the raw impression of sight does with the blink of the eye. What happens when you stare into the light too long? The image burns onto your retina while its opposite drifts inside your eye and your mind. This ‘drifting opposite’ becomes the only event. An event worth watching, as it moves on its own and then recuperates and reconstitutes in the very next glimpse. It is not a narrative progression but a continual looping back to what is – almost – the original scene.

Scientists tell us that if you paralyze the eye and prevent it from moving continuously, scanning the scene much like a small motion detector, vision dissolves into a field of white light. They say that the eye and the brain only register difference and change. What is known and familiar is quite literally invisible. They also say that it is impossible to locate the point of distinction where the cells of the optic nerve turn into the cells of the brain.

Something about rain

‘Is the work about being inside on a wet day?’, Jeremy asks in his essay for this book.

In some ways, what could be better? And: what else could it be?

I’ve loved rainy weather all my life. Perhaps it is because I grew up with it in Berlin, a city wet and grey more often than not. But, more importantly, because watching the rain begin to fall on a scene outside a window slowly inverts all of the space before my eyes. Small drops, then streaks and lines begin to articulate what started out as the invisible volume of air: the negative space in the scene. My attention moves and my eyes begin to focus on a plane that was previously unoccupied, a plane in space that only seconds ago had no mark to guide the eye. In a short time, that which was empty fills with thick dense lines as it obscures what was previously the view. Wet blobs fill the volume to which everything else now becomes the backdrop. The glass of the window becomes a flat plane on which a screen of drops run and pour with increasing insistence and density, separating the two quite different events. All spatial understanding is reoriented. The ambient sound of raindrops falling is not directional but comes from all around. Their insistent sound repeatedly draws our attention to the present moment. This, it seems to me, is a pretty interesting thing to watch and listen to, from ‘ … the inside, on a wet day’.

Martin, Timothy, What about perception, working title for a forthcoming collection of essays, some previously published in Uta Barth: In Between Places, Henry Art Gallery, University of Washington, Seattle, 2000.